Compendium of a series of 7 articles on the ongoing Great Game of metals, published during summer 2020 in La Tribune

Since antiquity, countries or cities have developed strategies of power and influence in the possession of raw materials. This is the condition for a strong economy and power in international competition. Today: why is it necessary for a state to have a Natural Resources Doctrine?

1 What is a Natural Resources Doctrine?

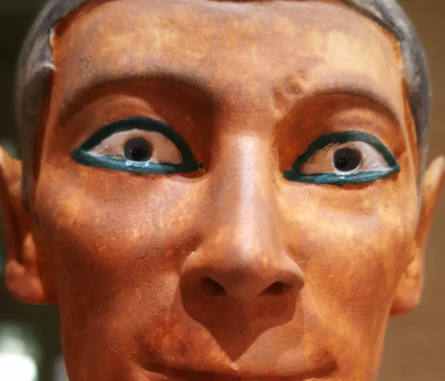

2,500 years ago, the Greek strategist Themistocles expressed undoubtedly the first Natural Resources Doctrine to serve a community. In this Athenian democracy of the time, he convinced his fellow citizens to pool the proceeds of the Laurion silver mine: 200 ships were financed, and the invader Xerxes was defeated in Salamis in 480 B.C. Most probably The Greek strategist Themistocles probably expressed the first Natural Resource Doctrine to serve a community.

His thinking was simple. Nowadays, we understand it as the expression of a Strategic Solidarity of defence of the City armed with a strategy of power applied to a precious metal deposit. It was extended by conquests, strategies of influence on its new territories, progress in science and philosophy, all facets of a luminous Athenian thalassocracy that marked its difference from the neighbouring cities and kingdoms.

Do we nowadays have such doctrines exercised by producers on their oil and natural gas reserves, on their wheat or rice harvests, or on their copper, nickel, cobalt, lithium or lanthanide mines?

Natural Resources Doctrine

Like this Athens, our States differed from one another because they each defined in their own way Natural Resource Doctrines, i.e. dependencies, independence and interdependencies with regard to these resources, and therefore their economies, but also their security.

Our countries are producers or consumers of raw materials and have adopted three doctrines: 1) the National Agricultural Doctrine and food self-sufficiency; 2) the National Energy Doctrine and energy independence; 3) the Mining Doctrine and national industry.

The absence of one of these will not allow a nation to harmoniously catalyze, with independence and sovereignty, a community of objectives and means to sustain its existence in the long term, it will have to rely on foreign territories.

The geopolitics of natural resources is this prelude to the political construction and economic development of States, this Great Game in which the national Natural Resources Doctrine of producer or consumer States are elaborated and then collaborate or confront each other. They each have very long-term trajectories, they are intergenerational Strategic Solidarities, which are rarely touched upon by successive governments and administrations at the head of countries, because they shape the special relationship between the population and its concept of nation.

Resource nationalism

This reading grid, which is personal to me, was developed from the 1980s onwards. For more than thirty years, it has shed light in its own way on how our States have been built through revolts, revolutions or more peaceful evolutions, leading to democracies, constitutional monarchies or “democratures”.

Here, producer countries exercise a strategy of power over their soils or subsoils, and this resource nationalism can be favourable or unfavourable to other countries, the consumer countries, depending on whether they are granted or denied privileged access to these raw materials. Here, consumer countries exercise strategies of influence to obtain supplies from producer countries, while also engaging in circular economy logics through recycling and more resource-efficient consumption.

2 What is the relationship between producing and consuming countries?

After the need for Natural Resource Doctrines in Episode 1, which ones are there?

Asian Doctrines are not the same as those we know in Europe and the rest of the world. There is a strong cultural difference in our relationship to the eternity of resource availability.

In general, North Asia has an active strategy in all three areas, as its local productions have long been insufficient :

Japan and Korea have sought and are still seeking stable supplies, both for energy and metals, particularly through long-term relationships with Australia, South America, and Southeast Asia; and for agricultural commodities with the whole world. The objective remains constant: to diversify supplies, substitute and recycle.

Modern China has developed its economy through its own resources, coal, mining and agriculture. All of this has taken the form of centralization of supplies, industrial consolidation and the fight against smuggling. With regard to the latter, the lanthanide epiphenomenon is an example revealed in 2010. Over-indebted public enterprises are the remnant of this model. Faced with immense needs, insufficient national resources and the adoption of strict environmental rules, the Natural Resources Doctrine has evolved towards more imports of raw materials; not by exercising a bellicose and misanthropic strategy of resource warfare against other countries, but through the exercise of its influence. This doctrinaire flexibility was facilitated by the training of Chinese leaders. It is easier to achieve the national goal when one understands the path to it. Of the last 6 presidents and prime ministers, with the exception of the current prime minister, Li Keqiang, a lawyer, all received thematic training as engineers. From 1993-2003, President Jiang Zemin and Prime Minister Zhu Rongji were electricians, then from 2003-2012 Hu Jintao was a hydro-electricist while his Prime Minister Wen Jiabao was a geologist, from 2012 to date, Xi Jinping is a process chemist and knows agriculture well.

This thematic chronology of Chinese leaders corresponds to the stages of the country’s development: power plants and coal, hydroelectricity and materials, geology and mining production which coincides, among other things, with China’s mining and energy geopolitical advances in Africa, process chemistry and agri-food investment. It is therefore no coincidence that it was the current president who decided to renounce to the doctrine of food self-sufficiency. Like other Asian countries, Korea or Japan, China has turned to agriculture of other continents. A recent accident proved him right. Following an outbreak of swine fever, which began in the fall of 2018 on its own farms and decimated its livestock, Beijing drastically increased imports of US pork products in the first quarter of 2019. But the trade deadlock with the United States forced it to tax these flows at a rate of 62% as of July 2018. As the conflict with Washington escalated, China turned to other countries, particularly in mid-summer 2019 to Europe and Brazil. As a result, world prices doubled. At the same time, China was looking to Russia for soybean supplies. Freed from a restrictive Food Self-Sufficiency Doctrine, China will have overcome this agricultural crisis.

While the word sovereignty is fashionable, China’s imports of minerals, energy and agricultural products are increasing the country’s dependence on foreign countries. Consequently, it is unstoppable that an embargo on its exports of certain raw materials, such as lanthanides in response to a crisis with Washington or another allied country on another issue, could lead in return to a series of blockades against its imports of other resources vital to its economy: pork, soybeans, lithium, cobalt, nickel, iron ore, gas … The world of raw materials is thus rarely a one-way street.

Non-Asian states are not anticipating much

Non-Asian states have selectively active Doctrines, and often they are not very proactive:

Europe has an Agricultural Doctrine, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), but it remains without a twin doctrine for energy and minerals because Brussels would have to assemble sometimes contradictory national policies. It would stop at the threshold of defining strategic energy and mineral materials: what does have in common strategic uranium of the French energy doctrine and German lignite, Polish coal or that of Eastern Europe? What about the replacement of this European coal by Russian gas or US LNG, each satisfying opposite requirements, which is strategic for Europe? Would we go for an inverted gas Yalta, Russian gas in the west of Europe, especially in Germany, US LNG in the east with Poland as an entry point for deliveries to Ukraine? What kind of new populism inspired not by political but by economic considerations is this situation leading us towards, since no energy geopolitics of the countries of the Union converge between coal, lignite, gas or uranium, and new energies are leading us towards technical and then economic dead ends? As far as mining doctrine is concerned, the problem should be simpler, despite Scandinavian production. Alas, Europe is in deficit on many metals.

The United States has largely lost its fears in thinking about natural resources since it has become the world’s leading energy power once again thanks to unconventional gas and oil. From a strategy of energy independence for a consumer country, they have migrated towards that of energy dominance for a producer country; it is therefore tempting for Washington to use this new pressure on Europe to counter the gas coming from Moscow; the setbacks of the North Stream 2 gas pipeline around the Danish islands in the Baltic Sea should be read in this light. The recently disarticulated oil market with a negative price on the future/physical delivery arbitrage as a symptom should be viewed from this angle: a geopolitical confrontation of an ageing vision.

The U.S. Mining Doctrine is only an embryo of apprehension for some metals of the military-industrial complex. However, resources have been catalogued on the national territory or in friendly countries, notably in Australia for the lanthanides; in addition, mining exploration centred on strategic metals is in gestation.

For agricultural commodities, States are buying under the aegis of a national doctrine: Qatar, Egypt, Mexico…

Finally and naturally, oil-producing countries in the Persian Gulf, mining countries such as Australia, Canada, DRC, Peru, Bolivia… produce and sell their natural resources under the aegis of producer doctrines. They will encourage investment in their production in order to maximize the national rent. This explains the willingness of the South African government and the platinoid mining companies to create an automotive catalytic converter industry in South Africa for export; it also explains the willingness of the Democratic Republic of the Congo to revise its mining code, which led to the creation of the concept of strategic metals to increase the rent; cobalt and coltan in particular have become strategic substances and their royalty has risen to 10%. It is also Indonesia’s expressed desire to become an industrial centre for the electric car, thanks to its nickel and cobalt mines. Finally, it is the unfinished Doctrine of New Caledonian nickel, propelled into a double impasse by errors in Parisian analyses and the lack of a common local vision.

The geopolitical balance of power between these countries rarely unilaterally favours the Doctrines of consumers or producers. On the contrary, the former gain privileged geopolitical access to resources and the latter benefit from the influence of consumer countries, in particular to develop their infrastructures or industries. This influence takes the form of transfers of knowledge and skills, the structuring of industrial sectors and production capacities and job creation. These are all essential elements for the acceptability of new mining and energy projects. In general, these two strategies of power and influence rarely oppose each other, a recent exception being the 1973 oil crisis and the following ones; but in the mining world, these two forces are often in balance on the map of the Great Geopolitical Game of Metals; this is already the case in nickel, for example, when Indonesia expressed its power by banning the export of minerals and Beijing’s influence allowed the establishment of Chinese factories at the foot of Indonesian mines. A similar movement cannot be excluded between batteries and South American lithium.

Dimensioning doctrines to projects

Companies often reflect the doctrines of their own countries: in Asia, the stakes are centralized, and companies are active in identifying risk areas and moving up the value chains. Elsewhere, particularly in Europe, the habit is generally to trust the markets and their intermediaries, the traders. Nevertheless, both identify their dependencies and apply their own doctrines to their projects. This is the case of car manufacturers such as Renault for the Zoé, BMW or Toyota who have, or will eliminate lanthanides from their electric models; it is the battery manufacturers who are reducing the cobalt content of their lithium-ion batteries, especially in the new nickel-manganese-cobalt generations of premium models. The same manufacturers are doing away with cobalt by choosing lithium-iron-phosphate batteries with lower power for the smallest models.

However, this win-win game may not work. Due to environmental concerns, the lanthanide producer Lynas had difficulties stabilizing its ore processing plant in Malaysia and the question of repatriating the refinery to Australia was raised. In other cases, the necessary skills are lacking in the producing countries, particularly on the African continent; or industrial porting is prohibited, for example in China when mining sectors are closed to foreign companies.

These strategies of power and influence are all the more essential to many States and to the post-COP21 and post-Covid-19 industrial sectors, since the shift in the energy transition is moving us from dependence on hydrocarbons to dependence on the metals needed to generate, transport, store and consume electricity in generators, connectors, battery chargers, accumulators and finally motors.

3 Which geopolitics for which metals?

After the description of the State Natural Resources Doctrines and companies in episode 2, how to think about the geopolitics of metals?

Again, we need to go back to the fundamentals to answer this question and remind ourselves that there are only four types of metals: abundant metals, sensitive metals, critical metals and strategic metals.

The tools of a national doctrine on natural resources have been widely used for the production and consumption of an abundant metal: it has been sought and discovered by a dynamic industrial fabric and inventive diplomacy. Then a range of technologies proved opportune to extract it from the ground, to refine it, and thanks to eco-design, to consume it in decreasing unit quantities and increasing uses; finally, it is recycled.

But this abundant material can become sensitive if one of the previous steps fails. This can happen, for example, when the demand for the material becomes inflamed, including for speculative reasons, and supply falls behind before catching up. For example, the prices of platinum and palladium in the 1990s, those of some lanthanides in 2011-2012, and lithium, cobalt and vanadium in 2018, each showed a bell-shaped price curve. Each time, a fundamental tension was accompanied by speculation, followed by a decline that the industrial buyer must be able to manage.

Questioning the balance between real supply and industrial demand

A material will be critical if there is a high risk of deficiency without a scientific breakthrough that opens the way to substitutions. But it will be critical in one industry and not in another, in one country but not in another, and this changes over time depending on the market fundamentals of that metal – such as the downgrading of lithium from a critical metal to a sensitive metal.

If the consumption of a resource accelerates (organic agriculture), or if an accident handicaps production (iron ore in Brazil following the collapse of dams), then criticality will persist in the medium term. The prudent consumer, with a long memory, will regularly wonder about these metals and the balance between real supply and industrial demand; otherwise, the danger is to freeze the criticality or, on the contrary, abundance without giving it a temporal dynamic.

Interdependence of “major metals” and their by-products

For example, one metal that will be critical to the future of the energy transition is undoubtedly copper, whereas, as we have just said, the lanthanides are losing their criticality to manufacturers who are banning them from their electric vehicles.

Moreover, if this metal is a by-product of a major metal, it is essential to observe the balance of the latter. Anticipating the fundamentals of the rhodium market is impossible without assessing the market for its major metal, platinum in South Africa and nickel in Russia. Its current small crisis over the period 2019-2020 is the fourth I have experienced – since 1990, there has been one every decade. They illustrate that the metals are and will be periodically under stress, but with few shortages, because to my knowledge no plant has ever failed for lack of rhodium.

Similarly, it is impossible to forecast the indium market without assessing those of its major metal, zinc; the analysis of gallium must first gauge the bauxite market and therefore the aluminium market; rhenium is a by-product of molybdenum itself, like cobalt, a minor metal of copper; neodymium is interdependent on the cerium market… Conversely, despite the simultaneous inflation of their prices in 2018, it is this structural difference between lithium (a major product) and cobalt (a by-product) that would allow for divergent expectations between these two components of electric vehicle batteries in the future.

Iron, copper, sand… abundant resources that have become “strategic”…

Finally, a strategic metal moves away from geological or market criteria. It is an indispensable resource for the regalian missions of the State, for national defence or for the essential political ambitions of a consumer or producer country. Thus, one of the most common materials on earth, iron ore, demonstrates that an abundant material can become strategic without becoming critical: indispensable to the steel used in China’s strategic urbanisation policy, it had become strategic there since the beginning of the century and reached its peak in 2008-2011. Copper for infrastructure and sand for concrete were of the same order.

In France, with the exception of uranium, which benefits from a law, a decree and classified directives, there is, strictly speaking, no other strategic material. At the European level, without a common policy, there are no European strategic metals because a material will be strategic for one European country but not for another, and this evolves over time.

Competitive consumption

If these last two notions, critical and strategic, merge, some minds imagine that wars will seize the tensions created around these metals that have become untraceable; they seek insights into past models of the Great Energy Game, particularly the one we have known for oil and/or natural gas for a century. The latter has more often than not adopted paradigms such as the Cold War, sometimes leading to real conflicts. However, this paragon does not apply to metals or modern agriculture. Our world of metals is not so bellicose that a modern state invades its neighbour with its army and unleashes a high-intensity war such as the first Gulf War, or that less vigorous tensions lead to the attack or seizure of oil tankers as in the summer of 2019 in the Strait of Hormuz, the drone attacks on oil sites in Aramco, and finally the intense trade war between Russia and Saudi Arabia in the spring of 2020.

Metals are multiple, flexible and substitutable in their uses, hydrocarbons are less so; metals are everywhere in the earth’s crust in varying concentrations, with more concentrated hydrocarbon pockets, although the possibilities of unconventional hydrocarbons have revolutionized this industry ; metals have associations, but no OPEC, which operates notably with the help of OPEC+ (OPEC plus non-OPEC members led by Russia); gas opposes two power strategies, those of the United States and Russia on the European market, but copper, aluminium, lithium, cobalt or lanthanides do not oppose any producing country.

Moreover, when this fusion between critical and strategic metals occurs, it leads to competitive consumption, that is to say, competition between different critical consumptions of this metal. The producer will favour the user closest to its own strategic objectives: in the first place, its domestic industry.

However, this situation can only be ephemeral: such a metal may not have been sufficiently researched in the earth’s crust, or it may be in ecological overconsumption, or even in evolution from the marginal metal stage to that of mature metal; these situations will generally be those of narrow metal markets, temporarily poorly managed and quickly falling into line. Thesis illustrated by the stratospheric prices of cobalt, lithium and vanadium in 2018. Their three bubbles have deflated as production, speculation, substitution and eco-design have taken their toll. A similar situation for the lanthanides in 2010-2012: tension, then calming once the bubble has burst.

4 The fake-news of “rare metals”

After the description of the geopolitics of metals in Episode 3, how did the fake-news organize its hold on politics?

Because it encompasses the policies of states and companies, the paradigm combining the fusion of critical and strategic metals and competitive consumption becomes geopolitical. It therefore runs the risk of being the target of fake-news. In the world of oil, everyone will remember the thundering fake-news, particularly at the United Nations, that accompanied the Second Gulf War. In this field, the world of hydrocarbons is well ahead of the world of metals.

In the past, the “palladium crisis” was very costly for the automobile industry, Ford in 2001-2002 lost 1 billion dollars; the “uranium crisis” of 2007 led to the Uramin affair which turned out to be a financial abyss of 2.5 billion dollars for Areva.

In both cases, the market was only the victim of manipulations without any real fake-news. More recently, in 2011-2012, the “lanthanide crisis” started as a production crisis, but it left a stigma in the valuation of stocks of Japanese processors who had bought against the current, and then, following fake-news, despite an initial warning, it ended with a warning from the Financial Market Authority and a judicial investigation.

In 2017-2019, with unprecedented vivacity, fake-news emerged in a new chapter: the “rare metals” or “untraceable”, such as lithium, cobalt or vanadium. Without any real production crisis, on the contrary, their prices rose to historical levels; but once reality was back in control, they collapsed. Perhaps we will see later on the harmful consequences of these price movements on strategic stocks?

From disinformation to fascination…

These fake-news phenomena work in cascades, one piece of disinformation causing the next. The first generally takes the form of fascination: the “rare” or “untraceable” metal that we could call “inobtenium”.

It focuses the attention of the politician of the producing country because he imagines it to be a geopolitical element in his strategy of power, while it hypnotizes the politician of the consuming country because he thinks it is a key to his strategy of influence. It is simply a myth, an oxymoron, a danger, an illusion that can have damaging consequences on the making of such and such decisions because they will commit the politician to a dead end bordered by misleading choices between such and such an industrial policy, such and such an energy policy or such and such an option for national security.

The example of the “Airbus of batteries” is an interesting one. This industrial initiative is undoubtedly an excellent way of catching up with Europe’s three world leaders, China, Korea and Japan. But why officially link the relevance of this event to “rare metals”, as a minister recently did? This statement is strange:

“In this sector, we must have the same logic: that of holding it from beginning to end. We are going to work on it, from the search for rare metals (with countries like Chile or Argentina), to the realization of the electric battery, through its integration in the car.”

What are these “rare metals”, indeterminate here? Given the two countries indicated, is it lithium which, thanks to upstream mining efforts and downstream R&D, is very far from being rare? Its price has collapsed and shows an abundance! Because of this illusion, the argument for an industrial verticalization of an “Airbus of batteries” loses considerable strength. On the contrary, the language of a more ambitious and forceful policy would have been: batteries freed from a dependence on “rare or untraceable metals”. This is why Lithium-Iron-Phosphate batteries are so interesting.

Avoiding mistakes, enlightening the politician

There are safeguards to avoid such mistakes and to enlighten the politician: data collection and analysis, and report writing. But these will lag behind the dissemination of the fake-news, and then the actions taken.

If a hoax comes from a partial, obscure, disparate, charge or discharge sweep, it is quick, it has the coherence and the attractions of purity, it is initially stronger than a complex and constraining truth that requires verification and patience because it is longer and more difficult to establish than an fake-news. The politician is generally in a hurry and will be, with few exceptions, a neophyte whose difficulty will be to reason truthfully about a virtuality, the “inobténium”, based on false elements. This misinformation, intended to produce over-interpretations and then emotions, causes errors.

Victims of these “fashionable subjects”, strategies of power and influence will distance the actions of States or companies from the realities of the markets. It is in this sense that the policy of untraceable metals is populist, because it leads to mistakes and deadlock.

This first “inobtenium” hoax generated a second fake-news, that of the culprit who is the originator of scarcity. This is nothing new. In the “palladium crisis” of 2000, Russia was accused of delaying deliveries of palladium in order to provoke a price increase, but the latter deflated just after the source of tension, TOCOM – the Japanese futures market, applied restrictions to its palladium contract. For “inobtenium”, the “rare metals” fake-news has its culprit, China. The forms of this culpability are diverse: a domination in certain metals, advances in the metals of the “red batteries” of “green electric vehicles” (cobalt, lithium, lanthanides) and the verticalization of industrial sectors.

First, there is the fake-news of the “politically correct” hoax, that of domination in certain metals. By dumping its own mining production, Beijing would gain a monopoly of certain punched metals that cannot be found – lanthanides, tungsten, etc -it would then stifle their markets in order to suffocate mines outside China. Then he would have them bought up by his own companies at low prices.

This message has the appeal of sensationalism fuelled by caricature: the culprit is China. But which mines would have closed as a result of a real and demonstrated Chinese misanthropic will? What is the evidence?

The simple reality of the nature of the underground

The reality is different. If the world’s leading copper producer is Chile, it is not the result of a belligerent geopolitical strategy towards competing producing countries, but because its subsoil is rich in copper ; if Indonesia, the Philippines, Russia, New Caledonia and Canada share the first places in nickel, it is also for a reason of mineralogy and not because they would be in a nickel war; thanks to its petrography, South Africa is first in platinum and rhodium, while Russia is first in palladium, and yet these two countries have an imbitable relationship; If the iron ore market is dominated by the Australia-Brazilian couple, it is because the pedology is favourable, the two countries are not at war; if Guinea supplies so much bauxite, it is not because it has wiped out other producers, but because it has resources; if China is first in lanthanides or tungsten, it’s not for a strangely misanthropic geopolitical reason, but again and again for a geological reason, it has rich deposits and it exploits them.

Other countries have deposits as large or as small, richer or poorer, but they do not exploit them. The example of the Salau tungsten mine in Ariège, France, is emblematic; it is undoubtedly world-class, but it remains unexplored and unexploited. Why is that? Just look at the news of June 2020, it is certainly not because of Beijing!

In conclusion, neither China nor any other country has economically waged war in order to bring down the prices of the metals it produces and consequently make mines in other countries disappear. This first idea of misanthropic Chinese domination is an fake-news, but no one is saying it.

5 The fake news and China, an ideal culprit

Fake-news fly in squadrons: after the “inobtenium” fake-news on politics in Episode 4, a second fake-news was that of the warlike Chinese mining advances. How did China become the ideal culprit?

First example, with cobalt from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). China imports a large part of the cobalt production of this country, the world’s largest producer. But how did the Chinese company China Molybdenum become the owner of the DRC’s largest cobalt mine?

A simple peaceful sale between two companies

Did she go to war, did she ask her army to intervene? Did it colonize or invade this territory? Did it use underground networks to bury the entire chain of decisions? None of these things. China Molybdenum simply bought in 2016 this giant mine from an American mining company… based in Phoenix, Arizona. A peaceful sale took place between two companies that had two different strategic visions of development.

But again, no one is saying that this factual information contradicts the fake-news of a Chinese cobalt war: if there really was a cobalt war, why would the United States have let the world leader go into Chinese hands instead of friendly hands? It was therefore necessary to wait for a private initiative in 2020 to demonstrate the fake-news: at the same time as opening a factory in China, Tesla contracted with Glencore, the leading Western producer in the DRC, enough cobalt for its production of electric cars.

The situation was identical when, in the midst of a trade war between China and the United States at the end of 2018, the world’s leading lithium producer, Chile’s SQM, saw 24% of its shares held by Canada’s Potash Corp being bought out by China’s Tianqi for more than $4 billion. Tianqi thus became the world’s largest producer thanks to investments in other producers in China and Australia.

Since it is recognized that Canada’s mining strategy has been in decline since the demise of Inco, Falconbridge and Noranda, we might ask ourselves why, if there had been a lithium war, would we not have seen a fight between a western company and Tianqi for SQM? Why didn’t Washington or Europe intervene?

The “Lanthanide War”, another false truth

Once again, the facts tell us that this is not a lithium war, but a peaceful private sale between two companies; the opposite is to talk about a hoax as long as no state has countered China’s advances.

Another false truth is the lanthanide war. China produces around 70% of the world’s ore, that figure is falling, and it refines it in its refining plants. Of the remaining 30%, only about 5% is refined outside China, the rest is exported to Beijing and processed in Chinese plants.

If there were a rare-earths war, what is this model of confrontation that would leave 95% of the world’s materials to one of the belligerents? Furthermore, the fact that one of the minority shareholders of the California mine at Mountain Pass is of Chinese nationality does not justify that this mine should export its production to China with customs duties that were raised to 25% during the trade war initiated by Washington.

Following the Molycorp episode of 2011-2015, if there had been such a lanthanide conflict, would the United States have been unable to finance a “war effort” of less than half a billion dollars and 300 jobs to produce permanent magnets on its soil from Californian ore or from deposits located in Texas, Colorado, Wyoming and Alaska?

It was only at the end of May 2019 that a statement by the US Ministry of Defence envisaged freeing up funds to reduce dependence on lanthanides of Chinese origin, particularly for military applications, and then President Trump put forward the far-fetched idea of buying Greenland.

As for the European future, if this lanthanide war existed, how would the same Chinese company that invested in Mountain Pass have managed, without European opposition, to contract the ore from a future mine in Greenland when the French plant in La Rochelle, closer by, could process it?

If there was a battle in this area, it was fleeting to say the least. One has to go back to 2009 to see that Australia protected its Lynas mine from a takeover attempt by a Chinese company, but conversely, in the same country, the Australian Yangibana mining project contracted the processing of its future production to Chinese companies. Once again, China is exercising its strategies of influence to source lanthanides, while no country is exercising a mining doctrine to counter its access to mines or its technical advances in ore processing.

When industrial reality belies the fake-news

Following a domination in certain metals, the subsequent fake-news is Chinese verticalization and its hegemony over a sector of activity. It is however based on the industrial reality practiced by all, the sector. If he gives himself the means to do so, whoever controls access to metal production dominates the downstream industrial sector. For thirty years, China’s huge leap forward has required large quantities of metals, and China, like other powers before it and for centuries, has exploited its territory. Then it imported by taking industrial and commercial positions in the metallurgy and mining industries of foreign countries, taking the risk of running up against local economic policies. This verticalization, far from clashing with the nationalisms of the resources of the producing countries, influenced their power strategies in order to reach compromises.

Thus, in 2009 Indonesia passed a law prohibiting the export of its mining resources without transformation from 2014, particularly to China. China has not gone to war with Jakarta.

On the contrary, it turned the crisis into an opportunity: six years later, in 2020, competitive Chinese metallurgical companies set up operations downstream of Indonesian mines. Crossing borders, Chinese industrialists have verticalized overseas from the extraction of minerals to the marketing of manufactured products within the same group, or even within an international supply chain, as in the case of CATL, LG and Tesla in Indonesia. Thanks to the alliance between Indonesian and Chinese mining doctrines, Indonesia is and will be a major global player in nickel for stainless steel and batteries.

The soundness of the verticalization strategy

Fake-news blames China for this verticalization strategy. But this is nothing new! Arcelor-Mittal operates in this way, from iron or coal mines to steel marketing; Korea’s Posco also by securing the loyalty of New Caledonia’s nickel ore; Finland’s Outokumpu by operating its own chrome mines for its steel; Norway’s Norsk-Hydro operates in the same way with its bauxite for its aluminium; and Michelin cultivates its rubber plantations for its tyres; Bonduelle buys farmland for its vegetables; Russia’s Rostec consolidates the arms industry and operates its own copper, gold, niobium and lanthanide mines; Nestlé builds up the loyalty of coffee producers for its capsules; the electricity company RWE consumes its lignite production in its power plants; Engie does the same with its natural gas. For their part, Chinese or Japanese car manufacturers do no other than control the industry, from the mining company exploring for lithium or cobalt to the marketing of electric cars.

Controlling upstream to better play a role downstream, the reality of verticalization contradicts the fake-news of Beijing’s innovative hegemony, especially in the electric vehicle. Here again, China fills the void left by the absence of our mining doctrines and can lower the country’s overall production costs. Moreover, critical and strategic metals professionals have long observed that Chinese initiatives in this field are provoking “capitalist competition” among Chinese private companies themselves, sending the conspiracy of a misanthropic Chinese strategy back to its origin, the hoax.

Various fake-news followed, such as the one opposing the circular economy, which seeks to harm the electric car by claiming that the “Chinese red batteries in green electric cars” are not recyclable. On the contrary, in Europe, the collection channels for these batteries of Asian origin used in European vehicles are almost all perfected; the incentive is normative rather than economic; the dismantling of the modules is labour-intensive and requires a minimum of automation; then, as metal refining is widely known, the industry will become more profitable as the volumes to be recycled become available.

Let’s stop there with these fake-news questions. Although, curiously enough, they all point to a single culprit, China, they demonstrate that it has not initiated a metal war, that, on the contrary, it has peacefully and commercially gained access to mines because of the emptiness of our own mining doctrines; but the question that needs to be asked is this: why these fake-newses, which have played on ignorance, emotion, and are celebrated among neophytes eager to receive information confirming only their established beliefs, why have they regrouped into a myth of “metal warfare”? Whatever the causes, this legend reinforcing the belief of a conflict has settled in the brains as in the nests of absent birds.

6 The cause of the fake-news

After the description of China’s place in the fake-news of episode 5, whatever the causes, the legend supporting the belief of a conflict in metals has settled in the brains as in bird’s nests absent for the wrong reasons, and we investigate three of them.

The first hypothesis is that of the decidedly anti-Chinese myth: it is a small facet of the immense trade war between the United States and China. The danger is that it calls for a belligerent response. Fortunately, no war has been declared over lithium or cobalt, and it is salutary that, with regard to the lanthanides, the Chinese president’s statements in 2019 about the imposition of an embargo on its “important strategic resources” following the US sanctions against Huawei have remained only declarations. Beijing has not responded to the accusations with an embargo on rare earths.

The danger of ideologies is the risk of excluding oneself from reality

The best we can hope for is a reversal of the fake-news, so that the beneficial effect of this return to reality will curb anti-Chinese feelings and appease a youth imprisoned by the feeling that nothing would be possible anymore to save the planet in the field of natural resources since China would be an enemy that would have already won.

As a result, the other benefit of the return of the truth would be a softening of anti-democratic feelings. Indeed, the models of the European Green Deal or the US Democratic Party are of such magnitude that they would be unworkable in a climate of real or virtual war for natural resources. However, the great danger that ideologies, and the political promises that support them, such as the ecological transition model, are in danger of excluding themselves from real life, of no longer understanding their impact on populations and of losing the link with the industrial world that produces these resources and with the world that transforms them. If it becomes impossible to keep these promises because they would have led to conflicts built on a myth such as the “metal war”, it is democracy in the broadest sense that suffers.

The energy transition needs the “peace of the metals”.

Words have a meaning, to use the word “war” without ever having experienced war is deplorable; we do not need an fake-news on a “war of metals whether abundant, critical, strategic, rare or untraceable” to save the planet, but on the contrary a truth on the “peace of metals” to negotiate without emotion. Only an inclusive cooperation of Beijing, Moscow and other producers of technology and natural resources, as Indonesia and China have achieved, will fulfil the promise of a European energy transition that no longer confuses rhetoric with reform.

The second hypothesis on the origin of the “metal war” fake-news is contiguous to the first. It is a dangerous myth, because it had an anaesthetic effect. Each state stood still, because each believes that China’s mining doctrine is being fought by someone else, since the fake-news indicates that a war would exist between China and that someone else. But this war is nowhere, this other one does not exist; no battle, even economic, has been fought recently specifically for copper, nickel, iron, platinum, rhenium, beryllium, cobalt, gallium, germanium, graphite, indium, niobium, lithium, lanthanides. No one opposed its influence and mining advances. This metal war is a decoy, it never took place.

Abandoning sovereignty in our mining doctrines…

This argument is often countered by lists of strategic or critical metals constructed by states. Unfortunately, they do not answer the question of a fight or a negotiation. They are neither evidence of a war nor weapons nor offensives, but on the contrary a kind of observation that should remain secret, a foolish intellectual surrender on the scale of a virtual “metal war” for want of a fighter. And while everyone thinks that someone else is fighting China, Beijing has progressed unchecked. No one has opposed its influence and its mining advances. Accusing China of a “metal war” was to facilitate its advances, because by condemning a symptom, the disease continued to flourish, while the cause of the evil remained hidden: the abandonment of sovereignty in our Mining Doctrines.

Eliminating the anaesthetic of a virtual war and virtually waged by others includes claiming that China has gained positions because other consumer countries have deserted the mines and industry. Less visionary, they have not reevaluated their sovereignties and their strategic metallurgical and mining Solidarities and have abandoned their strategy of influence.

If nothing is done, without new mining doctrines, the next accused, the next victims of fake-news may be mining companies, companies working in batteries, electric cars, solar energy, electronics, even under the alibi of Socially Responsible Investment and Environmental, Social and Governance criteria in the lithium, cobalt, manganese, nickel, tin, copper sectors… It is therefore necessary to build these mining doctrines while protecting ourselves by questioning future metal-related fake-newses.

Desire to “make the buzz” or “vanity of imposture”

Other theories on the origin of a “metal war” could be imagined, but let us mention a third and last one. It is not impossible that these fake-newses on the “war of the rare or untraceable metals” are the fruit of a desire specific to our age of communication: wanting to be in the caquettish current events of fashion effects, to acquire notoriety, to “make the buzz” with the ultimate goal of being recognized. We will summarize this last possibility under the term “vanity of imposture”.

Of our three suppositions, it is the simplest and perhaps the most probable, without denying that it was chronologically preceded by the first and then the second, as a segment of a larger operation, resolutely anti-Chinese and, nowadays, popular across the Atlantic.

7 Strategy of influence, strategic stockpile, recycling, exploration and ESG

After the cause of the fake-news in Episode 6, how do we develop a mining doctrine?

The industrial sectors deeply involved in the manufacture of energy transition products (wind, solar, battery, electronics, 5G…) are looking for tools to counteract dependency on metals through their influence strategies. Several principles present themselves to them.

One of the first possibilities is based on strategic stocks. It is necessary to separate the stocks that are useful for the regalian needs of States from those of companies. Regalian reserves must have clear rules for entry and exit, their composition must change over time according to market fundamentals; built for the long term, they are fragile because they have a duty to navigate on sight, anticipating a market environment where speculation reigns.

China, the United States, Korea, France, Japan and other countries have strategic stocks of various energy, metal or agricultural materials. These government stocks cannot be pooled with those of the private sector.

Such management was improvised in France during the 1990s, and resulted in the sale of PGMs to the international market in the aftermath of the first wave of high consumption of platinum and palladium in autocatalysts by domestic manufacturers. Conversely, as noted in Episode 2, this stock building is working better in Asia.

On the corporate side, stocks should be guided by their boards of directors. The latter must therefore have the necessary skills to handle them. Another option is the use of trading companies to manage stocks in industrial chains, and nothing illustrates this better than the observation of the role of Japanese sogo-shosha for the benefit of Japan Inc.

Urban mining (recycling) at the expense of immediate needs

The second way to meet the increase in demand is downstream of consumption. Metals travel several times around the world between the place of extraction, refining, industrialization and consumption, and then they start this path again after recycling. The classic loop of the urban mine begins with the consumer bringing his used appliances to the collectors, and ends with the separation of the metals from each other. However, this process is insufficient to meet demand for at least three reasons.

As long as the material to be recycled is available in 10 or 20 years when the current products reach the end of their life, recycling will take place later than the immediate needs. Secondly, the main characteristic of some mines is that they are polymetallic deposits: several metals are contained in the ore, for example the 18 substances extracted from the Norilsk Nickel mine in Russia; there is usually one major metal and minor metals. It is sometimes a feat of modern chemistry to separate them.

Recycling, on the other hand, exploits the urban mine; it is a deposit that can be characterized by a low-grade mega-polymetallic superlative. The number of metals mixed together is greater than what is found in nature, and these alloys are utterly unnatural. Chemistry will be all the more unable to separate them because, thirdly, thanks to eco-design, the quantities per unit to be recycled are becoming smaller and smaller, which is why recycling costs are becoming uneconomical. It is not the same thing to recycle the strapping of a carriage wheel three hundred years ago to make a new strapping of a new carriage wheel, as it is to recycle plastic, metals and all other materials from a mobile phone, an electronic card, a catalytic converter, a computer hard disk… however, and contrary to fake-news, the metals contained in batteries are known and can be recycled without difficulty.

Moreover, as a sign of the constant progress of ideas, a new phase of recycling consists of no longer processing used alloys, but rather of burning stages by directly reusing clean alloy scrap from the consumer sector, rather than refining each metal individually.

Revolutionising environmental, societal and governance criteria

The third way to meet demand is to increase production. The United States is more familiar with the mineral composition of the moon’s surface than with the presence in its own subsoil of raw materials useful for electric vehicles. Deposits of lithium or cobalt exist in the United States, as do deposits of lanthanides. Although we are also ignorant of the value of our subsoil in France, we would easily use the contradictory argument of controlling the production of the metal to dominate the downstream industrial sector. This is why securing supply will involve increasing exploration and national production by revolutionizing our environmental, societal and governance criteria.

This new situation will make it possible, on the one hand, to assess the ecological impact of mining projects, and on the other hand, to exploit only strategic and critical metals that are useful to the government’s policies and the industries of the future, and thus to curb the production of other metals. This new reading grid will be relevant for objectively deciding whether or not a tungsten mine in Ariège, a lithium mine in the Massif Central, a gold mine in French Guiana, or a lanthanide mine in Colorado, Wyoming or Alaska is of interest.

Conclusion

When we talk about the Great Game of Raw Materials, I accept that we have had wars over hydrocarbons, because the fight for oil and natural gas has sometimes taken on military overtones, as was the case during the Gulf Wars or very recently the spying games on European soil for Russian or American natural gas.

States have not invested with the same intensity in a Grand Game for copper, nickel, aluminium, zinc, lithium, cobalt, indium, platinum, palladium or rhodium. Over the past 50 years, these metals have not been stakes justifying military invasions. Therefore, talking about “wars of the metals” is a mystification when we parallel with hydrocarbons and check the facts of these markets.

However, thanks to the revelation of the Covid-19 pandemic, territorial integrity and the protection of populations can no longer be considered as the only two sovereignties to be defended. Finally, we recognize that States must be sovereign in matters of economy, finance, cyber, food, investment, biology, culture and also natural resources .

In order to understand this world of sovereignties in raw materials, we have evoked through our reading grid the notion of strategic solidarities: very long-term energy, mineral, agricultural, cultural, industrial, economic, digital, environmental and military trajectories that the various governments that succeed one another at the head of a country do not touch, because they shape the special relationship between the population and its conception of its own nation. This explains why some energy, agricultural or mineral debates are igniting so quickly.

These strategic solidarities differentiate States from each other because they define their dependencies, independence and interdependencies in terms of security, natural resources, economic development, health, economic models, etc. They are implemented through the doctrine of raw materials, i.e.: to dispose of oil, natural gas, coal, metals, mineral and agricultural products in order to transform them through industrialization. For example:

– when France decides to decrease its nuclear power production, it affects its energy doctrine, it should affect its doctrine on uranium, and it will affect its strategic solidarity linked to the price of electricity for the population and industry.

– Similarly, in Germany, with the planned phase-out of lignite and coal to reach 80% of electricity production from renewables by 2050. This double event will change the doctrines relating to Natural Resources and will initiate, on the one hand, a dependence on the storage of electricity and the metals concerned, and, on the other hand, on future gas consumption, with a conflict already present between Russia and the United States over the supply of natural gas to Europe. Political consequences with resurgence of nationalism or populism inspired by the economy are also already there.

– Similarly, when Europe embarks on a Green New Deal, or when Joe Biden plans to spend $2 trillion on a green infrastructure plan, they also touch on the doctrines of the countries of the Union and that of the United States on Natural Resources, and therefore on the need for new resources.

To be honest, I have yet to understand how the new European Green New Deal, which is the new European energy doctrine, or Joe Biden’s Green New Deal, will affect European and American sovereignty, how they will affect us, since this transformation is shifting our dependence on hydrocarbons towards a dependence on metals. The question is not whether we should replace a raw material (oil) with a metal (copper), but rather how can we ensure a meaningful energy transition without a European or US Mineral Doctrine consisting of strategies of strength over our subsoils or strategies of influence over the subsoils of resource-rich countries? Nothing is more conducive to populism than a broken democratic promise. Moreover, it seems to me that the danger is not a shortage of mineral resources, there will be some for our needs, but there are other more important questions about timing, price and Environment-Social-Governance (ESG) standards.

Indeed, in addition to the ongoing Chinese evolution, the geopolitics of natural resources in the 21st century will be under the influence of fake-news about two major issues.

First, with the urbanization of India, Delhi will be the great consumer of our century. The second axis is conducive to a new Great Game of Natural Resources of the 21st century, the self-consumption of the producing countries. Like the Saudi consumer, who was expected to consume more than half of the oil produced by his country, the formula “When the African consumer wakes up, China will tremble” expresses that African, Andean or South-East Asian countries will consume more of their own natural resources. Consequently, Europe needs to focus its thinking in two directions: to find a new strategic geological depth, and this geopolitical pivot of natural resources is most likely that of cooperation with Russia. The future will tell us whether the recent warming of relations between Paris and Moscow is a precursor to this.

The second parallel point is that the link between the geopolitics of metals and the ESG criteria surrounding the exploitation of natural resources must be revolutionised and eliminate the slag associated with its own financialisation. ESG must therefore standardise its non-financial criteria, for example deciding to exploit a mine according to the real usefulness of the metal produced, the consumption of water to extract it, or the displaced populations to make way for the miners, that is to say, in a way regulating good technical exploitation practices that protect the environment and all stakeholders. The relevance of these standards is sometimes impenetrable to the sciences of metrology when it comes to measuring environmental, human rights, social, community, territorial or governance requirements. ESG is a kind of literature that seeks its place in the middle of the engineer’s numbers. However, doesn’t a country that masters serious assets in this field of social sciences (philosophy, anthropology, sociology… etc.) have serious advantages if its companies are imbued with this national culture? A French Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), with its tricolored ESG criteria, will be different from an American, Japanese, Russian or Chinese CSR. Which one will be the best? The other interest of the tool is its superior capacity to decipher hoaxes, untruths, slander, false news and other fake-news. It’s an antidote, because it can analyse, explain and deny them. Faced with a society equipped with good CSR, lying becomes an uncertain thing.

The objective of this long seven-part article was to indicate that a State without a quest for sovereignty is not equipped for the long term by strategic solidarities, which themselves implement national energy, mineral or agricultural Doctrines. In the same way that an army safeguards sovereignty and strategic solidarities, it cannot operate without a doctrine and a strategy, it will be difficult for us to move in natural resources without a plan. This is why, if we want to enter, France or Europe, into the Great Game of Metals to ensure our sovereignty over these natural resources, we must first observe the terrain, eliminate fake-news, and then develop our own energy and mineral doctrines.